By Petros Tesfagiorgis

The ruler of Eritrea, Isaias Afeworki, has refused the COVID-19 supplies donated by the Chinese billionaire Jack Ma and his Alibaba Group. The plane carrying the goods was not authorized to land in Eritrea and returned to where it came without delivering the intended goods. Because of this the people of Eritrea will be paying a heavy price.

Monday 20 April 2020 the Covid-19 pandemic Global update was: Infected: 2.4 million; Deaths: 168.000; Recovered: 485,455

The figures above show that out of more than 2.4 million people affected by Covid-19 there is a good number of people who recovered. That shows government guidelines issued to their citizens to protect themselves from the virus is helpful. There are also other forms of support. For example, in UK there are more than 75,000 volunteers who deliver shopping to those who are sick and old. There are food banks that distribute food for free to the poor and there is financial help for those who lost their income and cannot pay their house rents and other bills.

In contrast, poor countries lack the resources and expertise to do the same. This was acknowledged globally and the rich countries felt responsible to provide help.

To that effect, the High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs, Josep Borrell said that “cooperation and joint efforts at the international level and multilateral solutions are the way forward, for a true global agenda for the future.” The EU has pledged to provide help worth more than €15.6 billion for countries across Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Balkan region to fight the coronavirus pandemic, of which €3.25 billion is to be channelled to Africa, including €1.19 billion for the Northern African neighbourhood countries.

The Prime Minster of Ethiopia, Dr Abiy Ahmed (PMAA) has written a long letter highlighting the consequence of failing to help the poor countries. He concluded, “We can defeat this invisible and vicious adversary but only with global leadership. However, this is not shared by his confidant, Isaias Afeworki.

This pandemic coronavirus is a global enemy that needs a global effort and commitment to defeat it. Sadly Isaias Afworki does not subscribe to this. He chose to be a pariah an outcast by design. Is it because getting international help demands monitoring and Isaias is against it, this is has become a serious issue among the Diaspora Eritreans

The decision of the Eritrean government not to accept help from the Chinese billionaire Jack Ma has worried health experts because Eritrea is not equipped to fight a pandemic. Meron Stefanos, executive director of the Eritrean Initiative on Refugee Rights, said to VOA: “Eritrea is not ready for anything. First of all, just eight months ago, Eritrea shut down 29 clinics run by the Roman Catholic Church.

Furthermore the Government of Ethiopia has ordered the closure of Hitsats refugee camp were 13,000 Eritrean refugees including 1600 minors live. To transfer them to the other crowded camps of Aba Guna, Mayaini and Shimelba on Lorries and buses having to drive for long distances is dangerous. Unaccompanied Eritrean Children are at risk in Ethiopia due to the country’s revised refugee policy, reports Human Rights Watch.

Another troubling incident is the decision of the Ethiopian Government to stop giving asylum to Eritreans. The repression in Eritrea is continuing unabated so why this change of policy at this time. This has given rise to all kind of conspiracy theories such as that Isaias has a hand in it. Many Eritreans asylum seekers unable to get any support from UNHCR are forced to beg in the streets of the town of Mekele, Shire and other towns in the Tigray region. The population of Tigray and the Government of Tigray region are doing their best to help. This is unforgettable act of sympathy and solidarity. It is the right way of building peace between the people of Tigray and Eritrea.

The regime do not want to close SAWA, a military training camp where the school leaving year, 12th grade, is taking place. In the camp thousands of young people from the age of 18 to 40 are kept hostages and are assigned to work for international mining companies, in construction sights and farms owned by corrupt high ranking army officers. It is a form of slavery. At the same time the regime claims they are there to defend the country from the threat of Weyan (TPLF) invasion. It is an escape goat to hold hostage the youth so they will not oppose the gross human rights violations in Eritrea. In SAWA people live in Dormitories in big numbers and eat in a cafeteria. If the coronavirus entered Sawa it is going to be genocide.

On April 6, the Heads of State of member countries of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) agreed to formulate a plan to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. The leaders of Uganda, Kenya, Djibouti, Somalia, and Sudan together with the prime minster of Ethiopia and the First Vice President of South Sudan held a virtual summit as the amount of confirmed COVID-19 cases keeps increasing in their countries. Eritrea was the only IGAD member state absent during the virtual summit. Isaias is scared that being a member of IGAD may require to abide by its decisions one of which could be to release prisoners. That will be unacceptable by Isaias.

It has become crystal clear that the priority of Isaias is to hide his crimes and bury truths and not to release prisoners and save lives. Family members and friends are not allowed to visit their loved ones in prison. More often than not they don’t even know in what prison they are kept and whether they are dead or alive. Some sources reveal that many have died and are buried in unmarked graves.

What is to be done? There is no other way except seize the most challenging momentum yet and call for action: There is no time the regime must be sued to face trial.

To sum up the Government of Eritrea has blocked any help to combat COVID-19. It rejected the United Nations appeal to release prisoners. It failed to close the training camp of SAWA. About 8 months ago it closed 29 health centres serving many villages and small towns. As a consequence how many sick people, including pregnant women are dying of lack of simple health care? The UN inquiry commission on Eritrea reported that the many violations in Eritrea are of a scope and scale seldom seen anywhere else in today’s world. The commission finds that crime against humanity may have occurred with regard to torture, extrajudicial executions, forced labour in the context of national service.

These are powerful set of crimes for which the regime has no defence when and if is brought to the court of law. To act along those line are the only way the just seekers can challenge the power of the regime.

There are information that explains the worst that could happen to the developing countries.

Coronavirus pandemic ‘will cause famine of biblical proportions’

Fiona Harvey Environment correspondent

I quote “Covid-19 is likely to be sweeping through the developing world but its spread is hard to gauge. What appears to be certain is that the fragile healthcare systems of scores of developing countries will be unable to cope, and the economic disaster following in the wake of the pandemic will lead to huge strain on resources”

The desperate situation in Eritrea is expressed in a letter sent to the UN by Daniela Kravetz the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Eritrea, highlighting the danger Eritreans are facing because of COVID-19. The special rapporteur is alerting the UN of the danger to Eritreans.

First and foremost, the Just seekers have to prepare well packaged manifesto of the already documented gross human right violations.

Second: It has to be remembered that when the UN inquiry commission reported all the crime committed in Eritrea, the UN did not take any action. It failed even to condemn Isaias let alone bring Isaias to court. Simply, Justice has been denied to the Eritrean people by the UN. It is a historical blunder. The UN encouraged by the peace reached between Eritrea and Ethiopia allowed Eritrea to be a member of the UN human rights commission. Isaias felt more empowered as to close the 29 clinics and imprisoned several Muslims. There are a lot of questions to be answered by the UN.

Third: The just seekers has another option. To go it alone and sue Isaias in courts in the West. It is possible to sue a governments by an individual or groups of individuals in courts in Europe – of a crime that involves thousands of people – in a form of class action. Class action can be brought by few people but could represent thousands of victims in the same case.

Take the example of Citizens for Peace (CPE) in Eritrea. Following the senseless Ethio-Eritrean border war of 1998-2000, CPA, to which I was a founding member was active in helping a group of American lawyers who initiated a class action case against the Government of Ethiopia on behalf of some expelled Eritreans whose properties were confiscated. The American Lawyers succeeded in convincing an American law firm to take the case to the US court. The legal hearing / proceedings had been set in motion. The Ethiopians said that they are ready to pay any compensation but there is already a commission regarding compensation and they will deal with it when the study is complete. They said they will cooperate with it and give compensation. Indeed there were 3 commissions. Boundary commission, Compensation commission and commission to study how and who started the war.

Belatedly more Ethiopians found out that Isaias hands are poisonous, instead of promoting peace in Eritrea and in Ethiopia he became the champions of hate, dishing out hate campaign against the regional Government of Tigray in collusion with the Ethiopian extremists like ESSAT.

The most important question is how do deal with it. I don’t have an answer to that but it worries me. There must a committee staffed with professional activists to run the show.

On the positive side many professional association have mushroomed among the Diaspora, The Eritrean Law society, the newly formed Eritrean women Association in USA who launched a successful conference in Washington DC. A noticeable growth in the confidence and determination of Eritrean women. One such positive thing of immense importance is the formation of Professional Associations composed of 95 Eritreans Ph.D. holders. There are many other activists such as Hidri Jeganuna, Eri-platform, Eritrea Focus, Network of Eritrean women in Europe. Most importantly the Eritrean youth. The youth are on fire saying enough is enough the regime has to go. They have established popular Eritrean Mass Movement “Yiakle” . There are also the contribution of the political parties.

On the negative side. There is a lack of action that became a handicap to move forward. It must come to an end. During the closure of 29 Health centres, the imprisonment of Muslims in masses and the campaign to refuse to go to SAWA by the youth in Asmara. Nothing was done to condemn the regime. The slogan of the justice seekers “the voice of the voiceless” still remains a slogan only. The just seekers have failed to seize such important momentums and build pressure on the regime and gain valuable experience in working together.

I was about to post this article to Assena.com when someone told me that Martin Plaut has twitted that the British and US Government have asked their nationals to leave Eritrea. Something is cooking. May be Isaias is losing control.

That makes even more urgent to act. Isaias is exposed more than ever and even the Ethiopians belatedly learned that he is a liability to them as well. Today the powerful media of Ethiopia is exposing the Human Rights violations in Eritrea. They are asking to clean his house first before he interferes in the internal affairs of Ethiopia.

We have to make clear to the world our objectives in shaping the highest values in Eritrea: Freedom, democracy, justice, equality, and respect of human rights, the rule of law, fairness and sovereignty. Also in peace with our neighbours.

I reiterate the people of Eritrea wanted peace with all Ethiopians and not minus Tigray. Yes, we have to keep on looking for ways to have real peace- not peace between leaders only but also between our people. A kind of peace that puts the welfare of the people centre stage. Peace is about re-conciliation, forgiveness, to use the language of peace and other forms of peace building exercises. After so many years of being victims of human rights violation we have to be champion of peace in the Horn. To be so is to reject proxy wars that is bleeding Africa.

The Eritrean Mass movement (Yiakl) are quick to establish charities to help the refuges mismanaged in Ethiopia COVID-19 Relief for help refugees is organised by Eritrean Community Connections. Let all of us be generous and help.

The End

Citizen for Peace in Eritrea (CPE) is a voluntary Association of concerned Eritrean citizens who have come together as a committee for the purpose of studying and disseminating information about the Ethio-Eritrean conflict and its human consequences.

![Can Eritrea's government survive the coronavirus? The coronavirus pandemic will likely spell trouble for Eritrea's authoritarian government led by President Isaias Afwerki, writes Zere [Feisal Omar/Reuters]](https://i0.wp.com/www.aljazeera.com/mritems/imagecache/mbdxxlarge/mritems/Images/2020/4/29/3aff8ced6fe648afa1c69504f500a2f6_18.jpg?w=840&ssl=1)

![President of the Sudanese Transitional Council, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan (C), walks alongside military officer during an army exercise on the outskirts of the capital Khartoum on 30 October 2019. [ASHRAF SHAZLY/AFP via Getty Images]](https://i0.wp.com/www.middleeastmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/GettyImages-1179155014.jpg?w=1200&quality=85&strip=all&ssl=1)

![Ethiopia plans to close Eritrean refugee camp despite concerns Eritrean refugee children play in the Hitsats refugee camp in the Tigray region near the Eritrean boarder [File: Tiksa Negeri/Reuters]](https://i1.wp.com/www.aljazeera.com/mritems/imagecache/mbdxxlarge/mritems/Images/2020/4/17/d488b21e4a6b4d1bb3b04c7faee0a612_18.jpg?w=840&ssl=1)

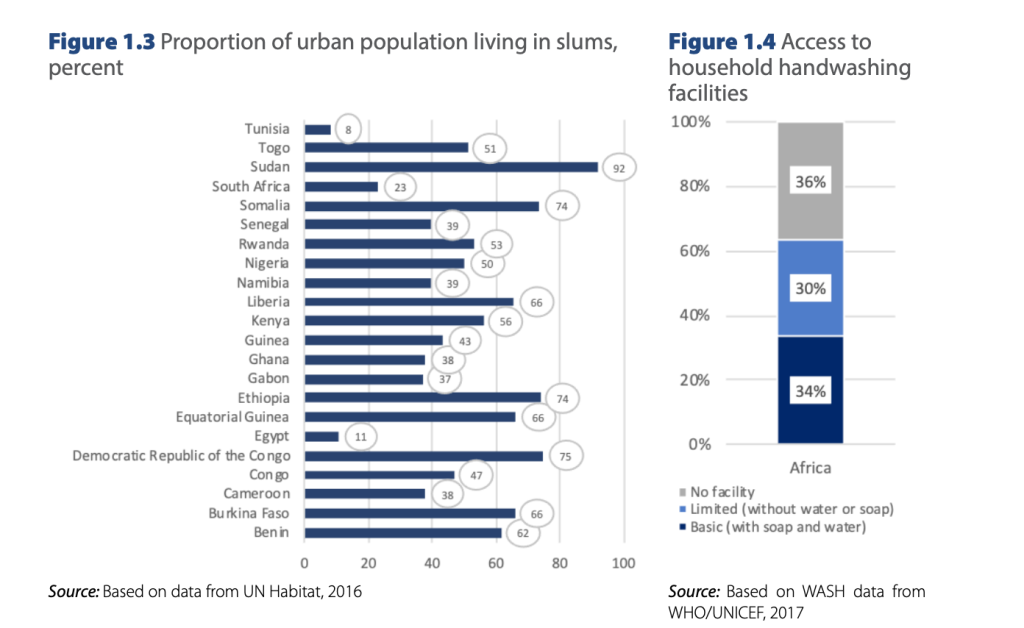

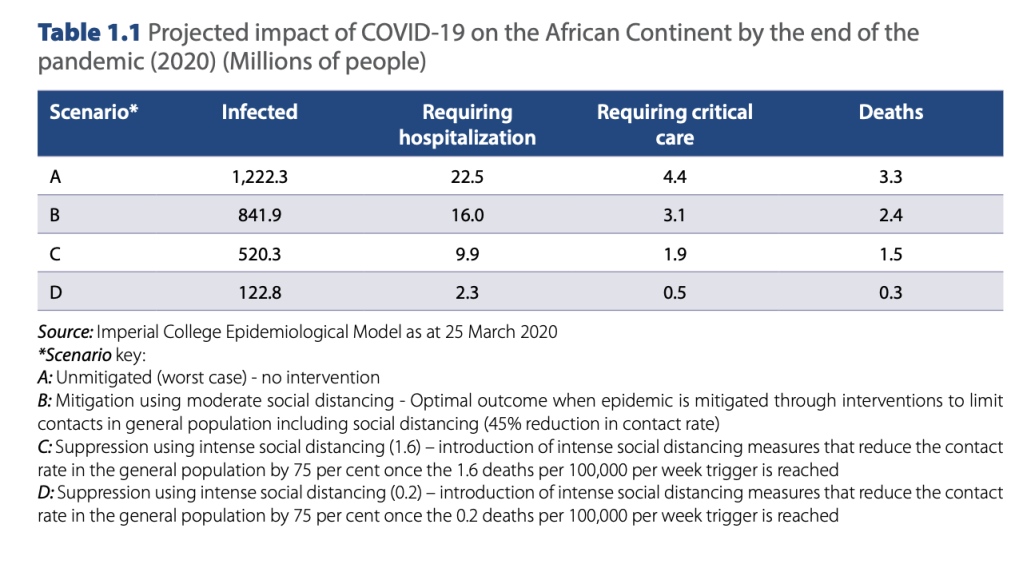

Africa is particularly susceptible because 56 per cent of the urban population is concentrated in overcrowded and poorly serviced slum dwellings (excluding North Africa) and only 34 per cent of the households have access to basic hand washing facilities. In all, 71 per cent of Africa’s workforce is informally employed, and most of those cannot work from home. Close to 40 per cent of children under 5 years of age in Africa are undernourished. Of all the continents Africa has the highest prevalence of certain underlying conditions, like tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. With lower ratios of hospital beds and health professionals to its population than other regions, high dependency on imports for its medicinal and pharmaceutical products, weak legal identity systems for direct benefit transfers, and weak economies that are unable to sustain health and lockdown costs, the continent is vulnerable.

Africa is particularly susceptible because 56 per cent of the urban population is concentrated in overcrowded and poorly serviced slum dwellings (excluding North Africa) and only 34 per cent of the households have access to basic hand washing facilities. In all, 71 per cent of Africa’s workforce is informally employed, and most of those cannot work from home. Close to 40 per cent of children under 5 years of age in Africa are undernourished. Of all the continents Africa has the highest prevalence of certain underlying conditions, like tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. With lower ratios of hospital beds and health professionals to its population than other regions, high dependency on imports for its medicinal and pharmaceutical products, weak legal identity systems for direct benefit transfers, and weak economies that are unable to sustain health and lockdown costs, the continent is vulnerable.