The first part of the research on the Horn of Africa described the regional state-to-state political dynamics, and now it’s time to delve into each country more in depth in order to acquire a heightened sense of their strategic positions. This will enable the final section about the Hybrid War vulnerabilities in the region to be more understandable to the reader, since a few of the scenarios admittedly require some detailed background information in order to properly comprehend the manner in which the US intends to effectively apply them.

Somalia

Overview:

This civil war-torn country appears to have passed the crest of its over two-decade-long crisis and is finally on the road to recovery, although it will likely be a prolonged and sinewy one that might take a few more decades to fully play out. At this stage, Mogadishu is struggling to assert its authority throughout the rest of the country, and herein lays the major hindrance to any effective reconstruction efforts. Somalia has been bloodily divided into a handful of warlord-ruled territories, neither of which really wants to cede their hard-fought sovereignty to the other, let alone to a central authority responsible for everyone. As a means of attempting to adapt to this reality, Somalia implemented a federal system in 2012, although it had transitional plans to do so ever since 2004.

Despite the US officially recognizing the Mogadishu authorities in 2013, it’s practically impossible to speak about a “national” government and likely will remain so for the indefinite future. The official military does not have the capacity nor the international support to simultaneously combat Al Shabaab terrorists (which have proved to be a very formidable and internationally destabilizing threat) and ‘federal warlords’, and the obviously pressing priority has thus fallen towards fighting the former. More than likely, Somalia will never return to the cohesive political unit that it once was prior to 1991, and this is a geopolitical reality that the federal government, its various warlord principalities, and the international community appear ready to accept and deal with. For as many challenges as it opens up, there are also a few opportunities for self-interested and ambitious actors to exploit.

Institutionalized Warlordism:

The major domestic factor that defines Somalia’s geopolitical future is its implementation of federalism, which in its particular context amounts to Institutionalized Warlordism throughout the country. There was no feasible way that the Mogadishu government was going to reassert control over the rest of the country ever again, and the rise of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) proved how radical non-state actors could actually become stronger than their host governments. In many ways, the rise of the ICU preceded the rise of Daesh, and it’s certainly appropriate to look at the two as being strategically and even tactically linked to one another in the grand sense. Separate from the rise of the ICU has been the autonomous and self-proclaimed independent statelet of Somaliland and its autonomous but non-separatist counterpart of Puntland, both of which the capital has had the highest degree of difficulty exerting its authority over. Whereas Puntland is still loyal to the Somali state, Somaliland endeavors to become its own separate country, and it already de-facto behaves as such. The other regions of Galmudug, the South West State, and Jubaland are more under the influence of Mogadishu than the aforementioned two, but the federal capital still does not have full and total sovereignty over their entire territory and all of its activities.

It must be qualified at this point that the regions which were just described are formed from some of the 18 separate legally recognized provinces within the country, and that while Somalia isn’t formally divided into a handful of different federal regions, the on-the-ground reality holds that this is the case and will likely remain to be so. Therefore, when discussing what the author has termed to be Institutionalized Warlordism, it’s important to remember that the regional constructs being referred to are not formally recognized by the 2012 Constitution but instead reflect the trans-provincial realities of Identity Federalism’s implementation to Somalia’s clan- and warlord-based realities.

Here’s an approximate map of the de-facto regional breakdown:

* Red: Somaliland

* Yellow: Puntland

* Red and Yellow Hashes: Disputed territory between Somaliand and Puntland, mostly controlled by the former at the moment

* Green: Galmudug

* Blank: Mogadishu and its surroundings

* Blue: South West State

* Purple: Jubaland

As can be gathered from the above, Somaliland and Puntland are critically important for controlling the Sea of Aden and the entranceway to the Bab-el-Mandeb that connects to the Red Sea. This explains why the UAE is purportedly building a naval facility in Somaliland, which is a lot more developed, stable, and independent than Puntland (which is where most of the notorious pirates from the last decade came from). The territorial dispute between these two statelets doesn’t seem poised to escalate into a large conflict, although if Puntland’s former president is successful in his bid for the national presidency, then he might obviously cut a deal with Mogadishu and perhaps even the international community (as represented most directly by the African Union forces in Somalia, AMISOM) to gain their support in making a militant move to settle this dispute once and for all under the pretense of promoting national unity and tackling secessionism. This would probably devolve into another phase of the country’s civil war and pull it back from the relative internal political successes that it’s made over the past decade.

In the more immediate future, however, Somalialand is expected to remain fiercely independent and will not unnecessarily cede any of its de-facto sovereignty to Mogadishu unless it gained (or thought it could gain) a lot more benefit than it believably loses by agreeing to this. Establishing that Somaliland is for all intents and purposes a de-facto yet unrecognized independent state and will continue to be treated as such by various self-interested actors such as the UAE, it’s appropriate to also talk about the other spheres of foreign influence that are popping up throughout Somalia and how they relate to the larger international dynamics of the Horn of Africa region. Jubaland, the purple-shaded territory along the country’s southwestern border, is the slice of Somalia that the East African state of Kenya unilaterally treats as its own, occasionally sending military forces and conducting airstrikes there to battle Al Shabaab. The forthcoming section about East Africa and which relates to that country in particular will explain the fear that Kenya has of Somali Nationalism and Al Shabaab, but for now it’s enough to just know that Nairobi envisions Jubaland as being its exclusive sphere of influence and one day operating as a buffer state in insulating the country from the rest of Somalia’s destabilizing woes.

As for the others, it remains to be seen exactly under which foreign powers’ purvey they will fall, but it’s reasonable to assert that Ethiopia will always have an interest in their activities. Looking back at the 2006 anti-terrorist intervention against the ICU, Ethiopia entered the country through the regions that are now generally identified as Galmudug, Mogadishu, and the South West State, thus underlining just how important Addis Ababa views these territories as its most preferred access route for directly influencing Somalian domestic events. It’s anticipated that this geopolitical reality will remain constant, although it’s unclear to what extent Ethiopia will be able to influence these regions in the future and whether or not it will ever stage another anti-terrorist intervention there. The latter scenario is only relevant if Al Shabaab launches a Daesh-like cross-border invasion aimed at establishing a terrorist ‘caliphate’ or if it stages some similar sort of provocation within the broad Somali Region (previously known as Ogaden). Should this transpire, then Ethiopia might end up repeating its 2006 operation and subsequently also occupying parts of the country for the proceeding next couple of years. This, however, is dependent on the military’s sustainable capabilities, and a domestic crisis such as a (preplanned and timed) separatist struggle against Oromo nationalists might force it to hasten an early withdrawal and concentrate more on responding to its most immediate and purely domestic threats.

To summarize, the implementation of Identity Federalism within Somalia’s specific domestic context and under its socio-political conditions has in effect institutionalized the warlordism that has been prevalent in the country for decades, and while this creates obvious challenges for the Mogadishu federal authorities, it also brings with it certain ‘opportunities’ for foreign states in most definitively carving out their envisioned spheres of influence. This state of affairs is most ‘mutually’ visible in the de-facto independent statelet of Somaliland, but it can also occur in any of the others, especially if a forthcoming domestic political crisis leads to them similarly cutting their established ties with Mogadishu and employing their respective militias in bloodily carving out a more ‘sovereign’ fiefdom within their territories. Also, the spheres of influence that were referred to might not always be ‘mutually’ agreed upon by the envisioned host region and their foreign ‘partner’, since as in the case of Kenya over Jubaland and Ethipia over Galmudug, Mogadishu, and the South West State, unilateral foreign action might be imposed out of furtherance of each intervening state’s subjectively defined self-interests.

The Scramble For Somalia:

This domestic geopolitical reality directly coincides with the abovementioned details about Institutionalized Warlordism, but deserves to be mentioned as its own separate domestic vulnerability and strategic factor owing to its large-scale importance. The UAE and possibly its fellow GCC partners are militarily involving themselves in Somliland, Ethiopia has a history of intervention and prolonged militarily presence in Galmudug, Mogadishu, and the South West State, and Kenya occasionally involves itself in Jubaland, which altogether proves that foreign countries are scrambling to delineate their interests in a centrally weak and broadly autonomous Somalia. That’s not all, however, since Turkey, like it was mentioned in Part I, is interested in setting up a military base inside the country too, albeit focusing on the Mogadishu Region. This would make it the second non-African state to have an indefinite military presence in the country, although of course the US’ secret drone bases mustn’t be forgotten as well. On top of all of this, the African Union (AU) maintains military facilities within the country as well, and it’s through the framework of the AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) that countries such as Burundi and Uganda have legally deployed their respective forces.

Scaling down the focus and moving from state to non-state actors, it’s worthwhile to once more bring up Eritrea’s UNSC-suspected role in supporting Al Shabaab terrorists and the link that this group has with Qatar. Addressing Asmara, it follows that it used (and perhaps still uses) this organization as part of its region-wide proxy war against Addis Ababa, while Doha sees in it a proxy army that could advance its respective ideological and geopolitical aims.

Again, there is no smoking gun that links either of these two countries to Al Shabaab without a sliver of reasonable doubt, but the existing arguments and provided evidence are convincingly enough to presume that some sort of connection between them did and likely still exists to a certain extent. From here, the analysis can thus proceed to the incorporation of non-state actors as agents of certain states’ geopolitical faculty, which thereby returns the focus to the regional federalized statelets and the interaction that states have with them and their respective militias (whether friendly such as the UAE and Somaliland or hostile such as during Kenya’s incursions into Jubaland). In accordance with the tenets of Identity Federalism that the author has written about before and periodically cited throughout the book, it’s expected that foreign states will intensify their state-to-non-state diplomatic interactions within Identity Federalized countries such as Somalia, and given the examined country’s geopolitical significance to global politics, it’s assumed that this will accelerate in the near and medium terms and usher in a competitive Scramble for Somalia.

Renegades:

The last driving issue in determining Somalia’s domestic stability is the role of Al Shabaab, which the author describes as a renegade terrorist group that disturbingly poses a latent regional threat on par with Daesh. The term “renegade” is applied towards the organization because it contravenes all established international norms and practices and is used by its two suspected partners of Eritrea and Qatar to destabilize the region in an unconventional way. Al Shabaab, just like Daesh, could one day turn on its previous partners and completely “go rogue” in becoming an uncontrollable source of trouble for every affected actor, be they its victims or former patrons. The interfusion of “Greater Somalia” nationalism, anti-Ethiopian sentiment (which could broadly be manipulated under the inclusive banner of “anti-imperialism”), and Wahhabi jihadism makes the group’s message attractive to misguided youth and mono-issue individuals who prioritize any of these three platforms above the rest of their life’s ideals. If Al Shabaab effectively harnesses the groundswell of support that it could possibly cull by exploiting each of these three unifying ideologies individually and then gathering them under the collective umbrella of their organization, then the terrorist group might receive a boost of support among some key constituencies and quickly rise to the level of strength that its ICU predecessor once wielded.

The renegade terrorist group would certainly succeed in prompting one, if not several, military interventions if it succeeds in gaining more prominence and power. For starters, Ethiopia would almost certainly intervene to a limited or all-out extent in order to prevent its Somali Region (formerly called Ogaden) from falling victim to the ideological contagion being spread by Al Shabaab. Kenya, too, would be compelled to do something similar vis-à-vis Jubaland, both to protect its own interests and also out of the regional leadership competition that’s playing out between it and Ethiopia.

Nairobi would not want to strategically ‘cede’ any square inch of its envisioned sphere of influence in southwestern Somalia to Ethiopia, the latter of which might broaden any forthcoming intervention to include that area as well. The African Union would likely get involved too, although its inner political mechanisms might prevent it from taking as immediate and resolute of a decision as either Ethiopia or Kenya, therefore making it the third most likely participant to directly militarily intervene, or in the case that it’s still present in the country at the time of this scenario (which is all but assured), beef up its forces prior to a robust offensive campaign. It can also be assumed that the US would play a Lead From Behind role via selected air/drone strikes, special forces incursions, and a strategic advisory to one, some, or all of the intervening militaries.

Considering all of the destabilizing “free-for-all” scenario branches that could predictably develop in response to Al Shabaab’s rise in Somalia, it’s fair to say that this terrorist organization represents the ultimate renegade factor in the country and perhaps in all of the Horn of Africa and, by Kenyan extent, to parts of East Africa as well.

Djibouti

Overview:

Tiny Djibouti has grown into one of the most geostrategic and competitively sought-after states in the whole of Africa, and this is entirely the result of its position along the Bab-el-Mandeb and its Chinese-financed railroad connectivity to the expanding Ethiopian economy. Its port facilities allow a handful of its closest military partners to assert their share of influence in behaving as the maritime ‘gatekeepers’ to Europe alongside of course Egypt and its control over the two Suez Canals.

The flurry of diplomatic-military attention that’s been given to Djibouti proves that there’s an active competition underway among various powers for equaling or at least approaching Egypt’s role as it regards the flow of European-Asian goods by way of the Red Sea. On a grand scale, this indicates that the world is cognizant of the dual maritime-mainland nature of China’s One Belt One Road policy, and that while the unipolar actors are frenziedly confronting it and attempting to block the mainland portions along the Russian frontier, they’re also simultaneously trying to do something similar in regards to the maritime one along the Bab-El-Mandab and Djibouti.

It’s not at all forecast that they plan on shutting down the waterway anytime soon, but it’s the potential latent capabilities that the US and its GCC allies are trying to attain (the latter of which were nakedly exposed in the War on Yemen) that signifies a strategic threat to the multipolar world on par with the one that’s posed to the Strait of Malacca and its related interregional connectivity function. For this reason, the concentration of focus on Djibouti is all the more important because this country has become host to so many varied military facilities by a handful of geographically diverse states, heightening the competition that’s been unleashed for advantageous access (and proactive safeguarding potential) to the Bab-el-Mandeb ever since the late-2000s “pirate” scare was used as the grounds for initiating the subsequent international naval scramble.

Too Many Cooks In The Kitchen:

As the saying goes, if there are “too many cooks in the kitchen”, it means that there are too many decision-makers in too small of a given space. This is the case when it comes to the multitude of military actors on the ground in Djibouti, which to review, includes the US, China, France, Japan, and soon Saudi Arabia. It can be understood that the unipolar forces will generally all align their intelligence operations against China, just as China will do against all of them in proactive response, but neither camp is expected to physically harm the other. Instead, Djibouti is turning into a spy haven and a forward operating base for drone, special forces, and other types of non-conventional involvement in the region’s affairs, to say nothing of the employment of conventional naval forces. With the small state being used as a springboard for the promotion of grand regional strategies, it could ironically be said that it is “to small to fail”, or in other words, it is too small of a strategic base for all of the involved powers that none of them can afford to shake its stability and risk undermining their respective self-interested deployment in the country.

Color Revolution Threats:

As is regretfully typical, however, it’s likely only a matter of time that a security dilemma will develop between the US and China, by which the Pentagon’s allies will bandwagon together in devising a plan to protect their military interests at the same time as they devise another one that’s aggressively aimed at undermining China’s. The US’ track record of destabilizations suggests that Djibouti is obviously not immune, despite the US and its allies’ military presences and related superficial interest in retaining general stability there. The driving motivation for the US to undermine the existing government of President Guelleh is to pressure him to either renege on his basing deal with China or replace him with a compliant stooge who will carry out the orders that he refused. Following the documented playbook of Color Revolution strategies, it can thus be expected that the US will soon start to stir up some Hybrid War threats against the government, and in this perspective the December 2015 anti-government riots can be seen as a warning to Guelleh of what might later come if he doesn’t abide by Washington’s wishes.

The blowback potential to this scheme is that Guelleh might end up ejecting their military bases instead of China’s if he is forced to fend off (with Chinese advisory or direct assistance) a serious enough Hybrid War threat to his government. Furthermore, even if the regime change operation succeeds in removing the President, his replacement might not be exactly who they expect it to be, or the selected individual might end up being preemptively swayed by China and thereby strategically neutralized in carrying out any damaging policies against its interests. The unpredictable circumstances that can thus (and as a rule, typically and in a chaotic fashion do) transpire through the unipolar commencement of Hybrid War might end up reversing the hoped-for strategic gains and ironically inflicting damage upon their creators. Djibouti is so important for unipolar strategy that the purposeful destabilization of the country isn’t a scenario that will be considered lightly by the pertinent decision makers who ultimately call the shots on whether or not to carry through with it, but conversely, because it’s also just as important (if not more) for China’s grand strategy, it’s possible that some of them might feel confident enough to initiate this dangerous gambit.

Afar And Somali Nationalism:

The Tripwire

In the advent of a breakdown in state authority, probably triggered by a Color Revolution and latent Hybrid War push by the unipolar Djiboutian-based intelligence units, it’s likely that the country might split into violently bickering identity groups along traditional ethnic-clan lines. Demographicallyspeaking, around 60% of the country is populated by the ethnic-Somali Issa clan, whereas roughly 35% is inhabited by the Afar, a transnational group of people whose territory spreads out across Djibouti, Eritrea, and Ethiopia (the latter of which has granted them a geographically broad federal state). It’s also important to note at this point that the former French colony in modern-day Djibouti was called the French Territory of the Afars and Issas in the 1967-1977 period immediately preceding independence, emphasizing the role that both people have played in the country for at least the past half century (if not obviously longer). Tensions between the two sides reached a violent climax in the 1991-1994 Djiboutian Civil War which saw Afar rebels fighting against the Somali-Issa government, but in the end the authorities and their numerically larger ethnic constituents prevailed and ethnic Somali/Issa clansman President Guelleh was elected in 1999.

It’s important to point out that the Afars mostly concentrated their civil war activity in the northern reaches of the country where they’re natively from, and that in today’s current schema, this would place the Ethiopia-Djibouti railroad outside of their area of forecasted operations should a second civil war ever (as unlikely as it may seem at the moment) break out in the future. Considering that the said railroad is the spine of Djibouti’s strategic significance to the African hinterland, it’s accordingly appropriate to consider how it could be geopolitically affected by reactionary (or even proactive) Somali nationalism within an identity-based Hybrid War scenario in Djibouti. As a result of historical-colonial circumstances and the 1977 independence of their own sovereign state, the Issa Somalis have cultivated a separate identity from their Somalian nation state and namesake compatriots, which themselves have been proven after the beginning of the 1991 civil war to be a lot more deeply divided than may have initially met the eye during the Cold War and Siad Barre’s decades-long 1969-1991 administration.

Identity Unity And Disunity

In many respects, Barre functioned as a socially stabilizing force in uniting or at least pacifying the disparate Somali clans just as Gaddafi did in relation to the Libyan tribes, and the forced removal of both leaders had devastating consequences for national unity. It’s uncertain whether Guelleh serves a similar personal function for Djibouti or not, but it’s predicted that domestic disturbances against him could be the trigger needed to once more divide the country along its Afar-Somali/Issa lines which of course have geographic north-south dimensions, respectively. If this somehow opens the presumably dormant Pandora’s Box of Somali Nationalism and revives the idea of “Greater Somalia”, then instead of Djibouti being the recipient of the now-fractured Somalian state’s irredentist ambitions, it could turn out that the tiny country or at least some of its more nationalist grassroots (possibly even unipolar intelligence-influenced) individuals actively push to initiate the expansion or ‘unification’ of Djibouti with Somaliland in order to maximize the proposed state’s geostrategic significance and fulfill their ethno-nationalist desires.

There’s nothing concrete to indicate that this is a topic of popular discussion in Djibouti or Somaliland, but the author takes his cue from the observed experience of “greater” nationalist projects all across the world and their activation amidst periods of domestic identity strife. Also, the presence of so many unipolar military forces in Djibouti might likely also hint that there’s a sizeable NGO (intelligence front) complementary presence as well which could be discretely working to promote this agenda. From the unipolar standpoint, an expanded Djibouti-Somaliland (if the latter agreed to it) would lengthen their strategic presence along the southern passages of the Bab-el-Mandeb and the Gulf of Aden, thus joining the Ethiopia-Djibouti railroad, the Port of Djibouti, and the Somaliland port of Berbera together under one de-facto geopolitical unit.

Scenario Branches

Nevertheless, this might incite a counter-reaction from the Afar, which could then agitate for their own independence, unification with the Afar Region of Ethiopia (and thenceforth the destruction of the Djibouti geopolitical unit), or possibly even some form of Identity Federalism within Djibouti in order to retain the extant borders of the unwinding state. If that potentiality turns out to be the case, then the Afar would acquire the sparsely populated and landmine-infested northern reaches of the Gulf of Tadjoura while the Somali-Issas would receive the southern and more populated reaches, with the capital and ethnically mixed city of Djibouti (and all of its military facilities) being a separate political unit in the shade of Old Cold War-style Berlin. In this construction, the Ethiopia-Djibouti railroad terminal would be in the separately administered capital zone while the rest of its path passes through the Somali-Issa region, but it’s a near certainty that the Afar would want to have some sort of profit-sharing agreement with the Somali-Issas in order to financially survive in their resource-lacking northern reaches (which also haven’t been rented out for military bases, at least not yet).

To wrap up the scenario forecasting that was just undertaken by the author, a Color Revolution and/or Hybrid War attempt by the unipolar forces to change the existing Djiboutian government and oust China’s military presence in the country could reopen the ethnic wounds between the Afar and Somali-Issa communities, possibly leading to either the dissolution of the Djiboutian state and its division into “Greater Afar” as a sub-state entity of Ethiopia (but which would for sure be opposed by Eritrea out of its fear of encirclement) and “Greater Somalia” or “Greater Somaliland” or the Identity Federalized internal partitioning between two or three separate entities. In all likelihood, regional and world powers would now allow Djibouti to simply dissolve and be divided between its two largest neighbors because of the effect this could have in upsetting the delicate balance between Ethiopia and Eritrea, and if this specific scenario was advanced, then it would probably lead to a continuation war between the two Horn of Africa rivals.

Al Shabaab Aggression:

The last strategic factor affecting Djibouti is the possibility of attack by Al Shabaab, which might exploit the Muslim Somalian identity of the most vulnerable segments of the pertinent 60% of the population in order to gain militant recruits for carrying out its indirectly anti-Ethiopian assault there. They were already responsible for a May 2014 suicide attack in the capital which prompted the UK Home Office to warn that the terrorists may be planning to target more Western soft targets inside the country.

This precedent proves that Djibouti is on Al Shabaab’s radar and it will probably remain there for as long as the organization is in existence. A Paris- or Mumbai-style all-out assault on the country’s capital city would immediately prompt a state of pandemonium, as each foreign military organization that’s based there scrambles to understand what is going on and devise the most advantageous and self-interested way that they can assist the nation’s security forces in responding to the crisis.

The resultant competition might be fierce and unfriendly, and uncoordinated anti-terrorist measures by the US and China, for example, could even lead to unintended incidence of ‘friendly fire’, further heightening tensions between the two global rivals. Al Shabaab, as always, is the ultimate agent of chaos in the Horn of Africa and it’s impossible to accurately predict within a given certainty just what it will do, the impact it will have, and the domestic, regional, and international responses that it would elicit.

Eritrea

Overview:

The third and last littoral state in the Horn of Africa region, Eritrea is peculiar by all international political standards. Like was discussed earlier in the research, it’s engaged in hostilities or been in heightened tensions with all of its neighbors, which has led to a siege-like mentality among its population that has been readily promoted by the government. For this reason and many others, Eritrea is commonly regarded as a “rogue state” by the international community, which also involves the UNSC. This security organ unanimously implemented sanctions against the country because of what was alleged to be Eritrea’s support of the Al Shabaab terrorist organization. While the sanctions were decried by some alternative media commentators, it’s indisputable that both Russia and China agreed to these measures out of what they felt were justifiable grounds for doing so at the time, and that the personalities criticizing Moscow for its behavior in this regard almost always purposely avoid doing the same thing to Beijing. So as not to sidetrack the research too much into becoming an analytical commentary on the subtle workings of tacit pro-imperial and anti-Russian “alternative” media voices, the author would like to conclusively summarize that the existence of UNSC sanctions as also agreed upon by the multipolar leading states of Russia and China have led to the “rogue state” stigma being applied to Eritrea.

The Red Sea state is rich in mineral resources but poor in living standards, and this is both a result of economic-administrative mismanagement and the priority that the state gives to military affairs over civil ones (as seemingly justified due to the siege-like mentality that was earlier touched upon). Eritrea is estimated to spend around 20% of its GPD on military affairs, which obviously eats an enormous hole in the national budget in order to defend against what it views as multi-vectored threats from literally every geographic direction. Partially because of the poor economic conditions inside the country and the large amount of GDP that it’s dedicated to the armed services, the Eritrean government is understandably hurting for cash, which might explain one of the reasons why it turned to the wealthy GCC in collaborating with them in their War on Yemen. For as right or as wrong as commentators may have felt that Eritrea was for its post-independence rogue-like behavior, whether as an expression of destabilizing aggression or resistant multipolar pride, it’s fair to say that by recently cooperating with the GCC, Asmara has unequivocally sided with a pro-American unipolar coalition in order to receive money, fuel, and the possibility of sanctions relief, a halt in the West’s “Weapons of Mass Migration” plot that’s been hatched against it, and possibly Gulf and other investment after positioning itself as a favorable though unspoken partner in this globally infamous campaign.

Near-Permanent State Of War With Ethiopia:

The first primary defining characteristic of Eritrea’s strategic situation is that it has been on near-constant war footing with Ethiopia ever since independence, and that this has come to literally dominate every aspect pertaining to the country. To recall the opening portion of the Horn of Africa research, the Ethiopian-Eritrean Cold War has stretched all throughout the region and is especially a factor in Somalia, which explains Asmara’s suspected cooperation with Al Shabaab. The perceived threat that a continuation war could break out at any moment necessitates Eritrea’s sovereign right to spend so liberally on military affairs and institute a forced and indefinite draft policy for its citizens. This latter decision will be returned to very soon when describing the effect of the West’s “Weapons of Mass Migration” on Eritrea, but as pertaining to the former, the country’s military expenses are not solely used on conventional investments. Instead, a good amount of Asmara’s strategic attention is focused on utilizing asymmetrical elements in offsetting the stability of the Ethiopian government, and this particularly takes the form of hosting a handful of secessionist and anti-government organizations.

The Transnational Tigrayans:

Out of all of the Ethiopian-originated groups that Eritrea supports, perhaps the most strategically affiliated are the Tigray People’s Democratic Movement (TPDM) which even the UN has accusedAsmara of assisting. While all insurgent organizations are destabilizing to various extents, there exists a certain strategic symbiosis between the Eritrean government and the TPDM, largely stemming from the transnational state of ethnic Tigrayans between Ethiopia and Eritrea. In the Red Sea state, Tigrayans are estimated by the CIA World Factbook to comprise a whopping 55% of the population, while in Ethiopia, where they have their own ethnic-based federal state, the same source lists them as being just 6.1% of the nation’s total, though it should be underscored that this means that there are almost two times as many Tigrayans by number inside of Ethiopia than in Eritrea. Also, the percentage figures don’t properly indicate the inverse importance that Tigrayans have played in recent Ethiopian history because the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) was the main driver of the anti-Derg resistance organization at the end of the Ethiopian Civil War and is speculated to be the most important component of the present-day governing Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF).

Interestingly, the TPLF was allied with the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF), so essentially what’s happened is that the two civil war allies have broken apart and assumed leadership roles of each of the rival states, adding a further dose of complicating drama to the Ethiopian-Eritrean Cold War. What this means, however, is that the Tigray Region of Ethiopia is seen by Eritrea as an especially vulnerable region owing to the cross-border spread of this ethnic group, but correspondingly, the same could also be said about Eritrea’s Tigrayan-inhabited areas vis-à-vis Ethiopian grand strategy. To add to that, though, it’s thought that the Ethiopian Tigrayans are more loyal to Addis Ababa then they’d ever be to Asmara because they are perceived as gaining a disproportionate advantage from their positions within the ruling EPRDF and are consequently not predicted to turn their backs on the government which benefits so much. However, due to the perception among some critics that the Tigrayans occupy too influential of a position in the EPRDF and the rallying potential that this can have for gathering opposition-minded civilians into anti-government manifestations, it’s also not predicted that Ethiopia at this time and given its presumed internal political leadership’s arrangement would risk launching a war against Eritrea on the stated behalf of creating a sub-state “Greater Tigray” (although this might in fact be the unspoken tangential result of any forthcoming successful war).

No matter how the Tigrayan factor is or isn’t used by either side of the Ethiopian-Eritrean Cold War, it’s inescapable to ignore that it’s one of the most emotionally charged elements between them and will likely continue to occupy an important and symbolic role in their strategic rivalry with one another.

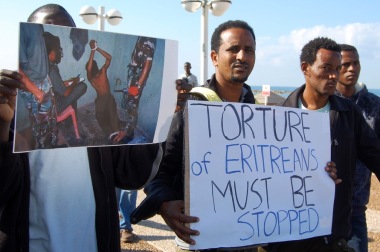

“Weapons of Mass Migration”:

Harvard researcher Kelly M. Greenhill’s groundbreaking 2010 research on “Weapons of Mass Migration” introduced the controversial concept that states were generating, provoking, and exploiting transnational human flows, and considering the documented lessons of what this theory looks like in practice, it can be confidently asserted that contemporary Western policy towards Eritrea applies various facets of this stratagem. There’s been a lot of negative coverage lately about the exodus of Eritrean “refugees” from their homeland and how this poorly reflects on the domestic conditions of their society, but while there are mixed reports about the accuracy of whether or not Eritrea is as bad of a “failing state” as it’s popularly described to be in the mainstream media, the large-scale human outflow from the country can objectively be attributed to two separate reasons.

The first one, to refer to what was touched upon previously, is the government’s policy of forced and indefinite military drafting of some of its citizens. It’s not the author’s place to comment on whether the “refugees” that “flee” from this policy are traitorous turncoats or future-focused opportunists, but it’s undeniable that the forced and indefinite draft is the reason why a substantial amount of people are leaving the country to never return. The other reason that needs to be mentioned alongside the same vein as the prior one is that European countries have a complementary and facilitative policy to this whereby they granted some sort of “protection status” to Eritreans between 91% and 93% of the timeon average. Undoubtedly, this almost guaranteed assurance that all Eritreans have of being given “refugee” or other “protection” status in the EU serves as a very powerful pull factor in magnetizing the high rates of out-migration from their country. Regardless of what the given push or pull factor may be, the UN refugee agency’s 2015 estimate that nearly 400,000 have left the country of slightly over 6 million people over the past 6 years speaks to the magnitude of impact that the West’s “Weapons of Mass Migration” policy has had on Eritrea.

The reason that the country is being targeted is because it has historically been reluctant to integrate into the Western-led international economic and political order, which to Eritrea’s credit, it has stoutly succeeded in doing up until the present day. Western countries and especially their most elite transnational corporations would like to access Eritrea’s wealthy mineral deposits with the preferential sort of conditions that they have elsewhere in the non-Western world, and Eritrea’s refusal to grant them this is what largely explains the West’s hostility to it and utilization of “Weapons of Mass Migration” in asymmetrically weakening its internal military, economic, social, and eventual political stability. Even so, as commendable of a brave and anti-systemic stand as Eritrea has made over the past two decades in that respect, this doesn’t excuse its UNSC-suspected support of the Al Shabaab terrorist group or its recent collaboration with the GCC’s War on Yemen. Instead, it can be argued that Eritrea’s sovereign choice to remain as far outside of the world system as feasibly possible put its government in the position where it had to eventually resort to such unscrupulous actions in order to sustainably survive. Looking forward, if the “Weapons of Mass Migration” that the West has used against Eritrea prove to be utterly devastating over the long run, then it’s possible that the country will either collapse entirely or bend progressively to the Western world’s whims, the latter of which might evidently have already begun as seen by Asmara’s willing participation in the War on Yemen.

Bad Friends, Bad Future:

Background Context

The final thing that will be discussed about Eritrea’s strategic position is its silent alliance with the GCC in their War on Yemen. The UN Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea released a report in October 2015 claiming that the latter “forged a new strategic military relationship with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates that involved allowing the Arab coalition to use Eritrean land, airspace and territorial waters in its anti-Houthi military campaign in Yemen” and that “Eritrean soldiers are embedded with the United Arab Emirates contingent of the forces fighting on Yemeni soil”. While Asmara has vehemently denied that it sent troops to Yemen, it has remained strangely silent on the allegations that it allowed the GCC to use its territory for striking its cross-sea neighbor. The author wrote two detailed analyses about this development for Katehon and The Saker, but the general idea in terms of how it relates to the present research is that Asmara has finally ‘come in from the cold’ and is now closely collaborating with one of the most aggressive unipolar military blocs in history, dramatically turning its back on whatever perceived pro-multipolar policies it had in the past and boldly charting a new geopolitical future for itself.

Changing The Game

That’s not all, though, since the new strategic relationship between Eritrea and the GCC which was forged by the blood that has been spilled in the War on Yemen is actually an ultra-destabilizing development for Ethiopia, which now has to contend with the very real and dangerous possibility that its foe has gained the military support of some of the Mideast’s most aggressive players. The aforementioned analyses describe this more thoroughly and should certainly be at least skimmed through by the reader if they’re genuinely interested in understanding what a potential game-changer this might become in relation to the strategic balance in the Horn of Africa, but the basic idea is that Asmara might seriously be cultivating its ties with the GCC in order to prepare for a forthcoming war of aggression against Ethiopia. It’s sensible to think in terms of this scenario owing to the siege mentality that Eritrea has been in over the past two decades and the utmost hate that its leadership has for Ethiopia, and even if it decides to launch its campaign simply due to the heated rivalry that it has with its opponent, this would have the most negative of repercussions for China’s Silk Road strategy in the region, especially if the GCC got involved in supporting Eritrea.

‘Plausible Deniability’

None of the parties acknowledge the UN’s report about their alleged military relationship, probably because of the sensitivity that’s involved due to the GCC’s much-needed strategic agriculturalrelations with Ethiopia, but that doesn’t take away from the very real military-strategic impact that they can have on the long-term stability of the region. If Eritrea decides on its own to go to war with Ethiopia or is pressed to do so by the US as a condition for the lessening of “Weapons of Mass Migration” pressure on the country, then if Asmara retains its nascent ties with its new GCC allies (and there’s no indication that it would willingly return to “rogue state” isolation and reject the monetary advances of its new ‘friends’), it will likely bring them into the fray as well. Qatar and possibly even Saudi Arabia by that time might have a very real interest in offsetting Ethiopia’s rise and tangentially obstructing China’s One Belt One Road geostrategic multipolar project in the Horn of Africa, which ultimately accords to the US’ grand strategy as well. As it stands, Ethiopia and Eritrea are relatively evenly matched, and this state of affairs has retained the cold and tense ‘peace’ between them since their latest large-scale conventional war in 1998-2000, but the insertion of GCC military-strategic capabilities into the equation on Eritrea’s side could dramatically upset the established balance and quickly turn the tables on Ethiopia.

The China Factor

In response to this unfolding potential threat, Addis Ababa may be compelled to enter into an arms race with Eritrea which would essentially amount to one against the GCC as a whole if they turn the former province into their personalized military outpost on Red Sea. In this case, Ethiopia would not be able to compete with the wealthy Gulf Kingdoms, but it could decisively shift the balance by intensifying its strategic relations with China and depending on any forthcoming security commitments that Beijing makes towards it. China wouldn’t be able to properly defend Ethiopia in the event of any GCC-related hostilities against it (even if they use Eritrea as their proxy), but its Djibouti-based force could present a tripwire deterrent towards the Gulf’s large-scale proxy escalation of conflict because none of its allied countries would have anything at all to gain by destroying their relations with China and targeting its military units which might by that point be sent to frontline advisory positions inside Ethiopia. An interesting twist to the security dilemma between Eritrea and Ethiopia can therefore be forecasted, in that the more that Asmara tries to bring in GCC support to bolster its capabilities (whether physical or strategic, potential or kinetic), the more that Addis Ababa can do the same with China, thus setting the stage for a possible prolonged GCC-China proxy confrontation in the Horn of Africa over influence along the Bab-el-Mandeb and its related continental interior.

Ethiopia

Overview:

The second most populous state in Africa is unquestionably one of its emerging leaders and a pole of attraction for Great Power competition and investment. Right now, China is Ethiopia’s unrivaled partner and is assisting its rise to regional leadership in all capacities. The Chinese-financed Ethiopian-Djibouti railroad and LAPSSET network to the Kenyan port of Lamu are instrumental in decisively surmounting the country’s landlocked geographic constraint and directly engaging with the outside world. Altogether, these two megaprojects will catapult Ethiopia’s standing from a regional force into a globally recognized power in its respective corner of the world, and their completion will create a magnet of incentives for foreign investors to compatibly boost its rapid development. Addis Ababa follows Beijing’s lead to such a tee that the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) is closely modeled off of the centralized administrative-political structure of the Chinese Communist Party. With China assured of its predominant position as Ethiopia’s prized partner of choice, it can thus work on maximizing the win-win benefit that it hopes to acquire from this relationship and help develop the country into one of the most dynamic economic nodes along the One Belt One Road global network.

Pairing nicely with Ethiopia’s envisioned economic leadership role in the coming future, the country has also demonstrated a proclivity in expressing diplomatic, resource, and military leadership as well. For example, Ethiopian diplomacy is very actively involved in bringing a settlement to the South Sudanese Civil War, and Addis Ababa’s plans in constructing Africa’s largest hydroelectric project, the Grand Renaissance Dam, will give it total control over most of the Nile’s headwaters and thereby enable it to exert strategic influence on Sudan and Egypt (much to their grumbling consternation and objections). Finally, Ethiopia’s 2006 anti-terrorist intervention in Somalia, while no doubt controversial and polarizing to some, showed that the country is willing to flex its military muscle when it feels it appropriate to do so. All of these leadership-evoking roles, whether assessed by various observers as being positive or negative in accordance with their personal viewpoints, objectively leave no doubt that Addis Ababa sees itself as one of Africa’s rising powers and a continental force to be reckoned with in the larger Horn of Africa-East Africa super region. In view of this, the factors affecting Ethiopia’s strategic stability can be seen as crucially important for all of its direct and immediately indirect neighbors.

In order to add some additional context to Ethiopia’s examined position, it’s highly recommended that the reader reference the author’s aforementioned Katehon and Saker works about the GCC’s anti-Yemen cooperation with Eritrea. The author expanded on some of Ethiopia’s strategic qualities within those articles and they could be useful in helping the reader acquire a more comprehensive assessment of the domestic situation there. Additionally, because the scenario of a renewed Ethiopian-Eritrean war was already discussed earlier, it won’t be reiterated in this section.

When Is A Federation Not A Federation?:

There’s no issue more important to Ethiopia’s domestic stability than the highly partisan one of its existing state of federalization. The so-called “opposition” (both unarmed and armed) state that the country’s form of government is insufficient in granting what they believe to be “equitable representation” to the country’s myriad ethno-regional groups. Even though Ethiopia is already internal delineated according to 10 identity-based regions and the separately administered capital city, they believe that this is nothing but a ‘farcical ploy’ in showcasing a pretense to ‘democracy’. What they’re actually advocating is the pressured transformation of Ethiopia’s centralized federation (a political oxymoron of sorts) into a loose and disjointed Identity Federation that would function as a collection of quasi-independent statelets and undermine all of the leadership advances that Ethiopia has undertaken in over the two past decades. To be sure, there’s definitely a monetary incentive that the envisioned ethno-regional fiefdoms’ leaders and aspiring elite have in seeing this occur, since they’d be able to more closely concentrate their respective entity’s natural resource and human capital profits into their own hands as opposed to having to share it under the present arrangement with the rest of the country in accordance to Addis Ababa’s centralized guidance.

This draws into question what the exact nature of Ethiopia’s present federalized arrangement actually is if it’s not autonomous enough to the pro-Western Identity Federalists’ liking. Interestingly, broad structural parallels can be made to the effectiveness of Ethiopia’s model of federalism and that of the US, since both are in essence federalized models that satisfy certain symbolic criteria for their respective constituencies but inarguably retain very powerful centralized cores that have the overriding and final say on the most important elements of coordinated domestic affairs. That is to say, Ethiopia and the US are “federations” in the technical textbook definition sense of the word, but they don’t function in the manner that many people have rightly or wrongfully come to stereotypically expect from such a system. This is the bone of the externally provoked domestic contention that occasionally flares up in Ethiopia, since the existing federal system itself efficiently works to its full potential but does not legislatively manage itself in the manner that some of its citizens have falsely been misled by the US and others into believing is the “proper” way that a federation should run.

Internal Anti-Systemic Threats:

The EPRDF’s centralized federal system that’s actively practiced in Ethiopia is under threat by two complementary Hybrid War forces that regularly conspire against it and which can by theoretical definition be divided into their constituent Color Revolution and Unconventional Warfare components, however, the country’s circumstances are such that there is more often than not a strategic-tactical blurring between these two parts. For example, the Ginbot 7 “opposition group” is regularly presentedto Western audiences in a favorable light but is in reality a self-described “armed” organization, or in other words, a domestic regime change terrorist network that is also suspected of having ties with Eritrea. What would otherwise be a purely Color Revolution vanguard group had it not self-described itself as “armed” and admitted to taking up weapons to violently overthrow the government is in reality a doubly dangerous organization, in that it functions as a ‘publicly presentable’ international face for the anti-government ‘protest’ movement but also simultaneously carries out very clear Unconventional Warfare goals. Being the closest that Ethiopia has ever come to having a leading Color Revolution organization yet not tactically ‘pure’ enough to fully be described as one owing to its stated terrorist agenda, it can be generalized that the regime change conspirators have conclusively decided that all anti-government groups must have some sort of Unconventional Warfare attributes in order to immediately transition into Hybrid War battle mode at a split second’s notice.

What makes Ginbot 7 unique though is that it is technically not tied to a given ethno-regional identity and claims to be broadly inclusive of all potential members that it can cull from the domestic Ethiopian pool. This stands in contrast to the more traditional Hybrid War organizations such as the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) which are generally tied to a given demographic, the Oromos and Somalis respectively. Concerning the first ethnic group, the rioting protests that some of its members initiated at the end of the year and which the author analyzed at the time have been accused of being linked to the OLF and Eritrea, which if true would be a reverse tactical application in which a generally Unconventional Warfare group engages in Color Revolution techniques and not the other way around like with Ginbot 7. It’s worthy at this moment to mention that the Oromo are the largest ethno-regional plurality in Ethiopia and that some of its members aspire to use this demographic fact to attain internal hegemony over the rest of the country, so the related doctrines of Oromo separatism and Identity Federalism are appealing to a certain segment of this group for these very reasons. However, no single terrorist group is strong enough to defeat the EPRDF and the Ethiopian military on their own which is why some of them have united into a semi-organized front, such as last May when the Tigrayan People’s Democratic Movement (TPDM), Gambella People’s Liberation Movement (GPLM), Benishangul Peoples Liberation Movement (BPLM), Amhara Democratic Force Movement (ADFM), and Ginbot 7 came together under an unnamed umbrella.

Assessing the state of Ethiopia’s strategic stability, the authorities must properly confront Hybrid War terrorist groups that masquerade in front of the global cameras as “pro-democracy” and “pro-federalization” ethno-regional-based civilians, but which can quickly reveal their true colors as lethal Unconventional Warfare foes capable of inflicting inordinate damage to the state system. Although the US has publicly distanced itself last year from such terrorists as Ginbot 7, OLF, and ONLF by stating that it does not support the use of armed force (especially by these particular groups) to overthrow governments, its hypocritical actions in Syria and elsewhere prove that this was nothing more than a public relations gimmick and likely presages that Washington is in fact actively cooperating with these terrorists but has wanted to present a semblance of ‘plausible deniability’ in order to proactively cover its tracks. The Hybrid War threat posed by these organizations is a difficult one to respond to, but Ethiopia has no choice but to rise to the existential challenge and face this major problem, as it’s predicted that this danger will probably become even more acute in the coming years as China solidifies its One Belt One Road influence in the country and Ethiopia naturally becomes recognized as one of the continent’s up-and-coming regional leaders.

Foreign-Originating Unconventional Threats:

Ethiopia is obviously under threat from Eritrea’s myriad intrigues that are aimed at undermining its leadership, but having already covered that in the previous section, it’s necessary to speak more about the other dangers that it’s facing. There are generally only two others that are significant enough to talk about, one of which has already been explored pretty comprehensively thus far. Al Shabaab is obviously a major threat to Ethiopia’s stability, although Addis Ababa can be applauded for keeping the organization outside of the country and largely contained to Somalia. It can be assumed that there are some terrorist cells residing in the Somali Region (formerly called Ogaden) and possibly even some attempted attacks that have been thwarted at the last minute over the past couple of years, but by and large, there doesn’t seem to be a considerable Al Shabaab presence in the country in spite of the presumably porous borders that Ethiopia shares with Somalia. The Daesh effect in using social media and other information-communication technology tools to propagate the terrorists’ message is mostly inept in this part of the world because less people are plugged into these platforms than they are elsewhere across the globe, which thus mitigates the potential for this occurring but of course doesn’t preclude it from eventually becoming a sizeable threat sometime further down the line.

There’s no ‘rule’ saying that Al Shabaab has to concentrate on recruiting the Somali community in Ethiopia or targeting areas within its namesake region, although these will predictably remain its areas of focus. That said, it’s very possible that the terrorists could be planning and eventually end up carrying out a large-scale attack across Addis Ababa or other larger cities within the country, and it can’t be excluded that they could team up with some of the many ethno-regional Hybrid War groups throughout Ethiopia in maximizing their collective chaos potential. Depending on the severity of any possible Al Shabaab attack, Ethiopia might be pressured to once more stage an anti-terrorist intervention into Somalia, although this time it might be of a considerably lesser scale and for a much briefer period of time than what it did in 2006-2009. It would of course have to exercise caution so as to not get itself caught in a debilitating quagmire that could unbalance its security forces from dealing with pressing domestic threats such as those from Ginbot 7 and its terrorist allies, so this policy option would have to be utilized judiciously and only in the most extreme cases. Be that as it may, the nature of Al Shabaab’s threat is that it’s so entirely unpredictable and always recently results in a highly publicized incident (e.g. the Westgate shopping center and Garissa College attacks in Kenya) that Ethiopia might have no choice but to launch some sort of symbolic attack in Somalia regardless, no matter if it’s purely superficial and not tactically helpful.

The other main foreign-originating unconventional threat is the potential for South Sudan’s violence to spill over the border and destabilize Gambella Region. The UN refugee agency reported that Ethiopia “became the largest refugee-hosting country in Africa” in August 2014 after more than 190,000 South Sudanese refugees cumulatively had streamed into the country, many of which entered into Gambella. This frontier territory is estimated to have only around 300,000 people, and yet the UN accounted for 271,344 South Sudanese refugees being located there on 1 April, 2016. It’s clear to see that the region has been overwhelmed by what might also be cynically functioning as “Weapons of Mass Migration” in attempting to trigger a centrifugal identity reaction in tearing apart Gambella and the neighboring diverse Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR). The SNNPR is a quilted patchwork of various tribes and ethnicities and is the area of Ethiopia which most closely bears a structurally identity diverse and potentially conflict-prone resemblance to South Sudan. The incipient danger is that the structural destabilization that the refugees might inflict in Gambella could spread into the SNNPR and be taken advantage of by Ginbot 7, its allies, and Al Shabaab in order to throw Ethiopia into the burner of full-scale and nationwide Hybrid War violence, putting the authorities on the defensive in all fronts and inevitably leading to one or another regime change group making relative gains on the ground in the immediate aftermath.

To be continued…

Andrew Korybkois the American political commentator currently working for the Sputnik agency. He is the author of the monograph “Hybrid Wars: The Indirect Adaptive Approach To Regime Change” (2015). This text will be included into his forthcoming book on the theory of Hybrid Warfare.

PREVIOUS CHAPTERS:

Hybrid Wars 1. The Law Of Hybrid Warfare

Hybrid Wars 2. Testing the Theory – Syria & Ukraine

Hybrid Wars 3. Predicting Next Hybrid Wars

Hybrid Wars 4. In the Greater Heartland

Hybrid Wars 5. Breaking the Balkans

Hybrid Wars 6. Trick To Containing China

Hybrid Wars 7. How The US Could Manufacture A Mess In Myanmar

Child asylum seekers in France have been left frustrated at the length of time it is taking to have their claims processed. Photograph: Thibault Camus/Associated Press

Child asylum seekers in France have been left frustrated at the length of time it is taking to have their claims processed. Photograph: Thibault Camus/Associated Press https://martinplaut.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/torture-eritrea.jpg?w=760&h=504 760w,

https://martinplaut.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/torture-eritrea.jpg?w=760&h=504 760w,  Holot detention facility in the Negev Desert, in Israel housing some 2,500 asylum seekers mainly from Eritrea and Sudan [Jim Hollander/EPA]

Holot detention facility in the Negev Desert, in Israel housing some 2,500 asylum seekers mainly from Eritrea and Sudan [Jim Hollander/EPA]